Superman Was Always ‘Woke’: Truth, Justice and the American Way

When James Gunn’s Superman soared into theaters on July 11, 2025, the movie landed an 83 percent “fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes, an “A-” CinemaScore and a $125 million opening weekend—more than enough proof that audiences were ready for a hopeful Kryptonian reboot.

What they were not ready for, apparently, was the déjà vu. Within hours, the usual culture-war choruses were accusing Gunn’s film—and by extension its square-jawed hero—of being “woke,” “soft” or somehow treasonous to the source material. The irony, however, is delicious as the only thing truly retro about this Superman is the backlash itself.

Eighty-six years ago fascists were already denouncing the Man of Steel as political propaganda. They were right then, and the present-day claims are right now: Superman is political, proudly so—because he was invented to punch bullies, not to placate them.

The Original Social-Justice Warrior

The character’s anti-authoritarian DNA was hardwired by two Depression-era teenagers, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, sons of Jewish immigrants who had fled Eastern European pogroms. In Action Comics No. 1 (1938) Clark Kent vows to become “Superman, champion of the oppressed.” The promise was more than marketing copy. With Hitler annexing Austria and the Ku Klux Klan flexing in America, Siegel and Shuster gave their alien refugee a single directive: protect anyone the strong wished to crush.

They soon let him off the leash. In a 1940 newspaper strip titled “How Superman Would End the War,” the hero kidnaps Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, hauling them before a League-of-Nations tribunal. Nazi propagandists were apoplectic. Das Schwarze Korps, the SS weekly, blasted Siegel by name for “brain-poisoning” American youth and banned Superman comics throughout the Reich. When today’s pundits complain that Clark Kent espouses “basic human kindness,” they may not realize they’re echoing Goebbels’s ghost.

Readers in 1938 didn’t see laser eyes or alien invasions; they saw a Depression-era crusader tearing through loan sharks, strike-breakers and lynch mobs. One month he bulldozed a wife-beater through a boarding-house wall; the next he tossed corrupt lobbyists onto the Capitol steps. Before America entered World War II, Superman forced a profiteering arms dealer to fight on the front lines of the conflict he’d stirred—then brokered peace between the warring generals. To brand that record “apolitical” is to miss the cape for the symbol.

The slogan “Truth, Justice and the American Way,” coined on radio in 1942, was a reply to fascism. The “American Way” Siegel and Shuster imagined was pluralistic and immigrant-friendly, the opposite of blood-and-soil nationalism. DC’s recent tweak—“Truth, Justice and a Better Tomorrow”—merely updates the syntax, not the sentiment

A Whole League of Anti-Fascists

Superman did not fight alone. In March 1941, nine months before Pearl Harbor, Captain America No. 1 hit newsstands with Steve Rogers decking Hitler on the cover. Like Siegel and Shuster, creators Joe Simon and Jack Kirby were Jewish; they received death threats from American Nazi sympathizers and required police protection outside Timely Comics’ New York office.

That December, psychologist William Moulton Marston introduced Wonder Woman, an Amazon who rescued a downed U.S. pilot and lassoed Axis spies while modeling what Marston called “strong, free, courageous womanhood.” By war’s end, superheroes were selling war bonds, cheering scrap-metal drives and appearing on military morale posters. The War Department shipped comics overseas alongside socks and cigarettes. Pop entertainment had become enlisted cultural artillery—voluntarily.

Politics Are Kind of the Point

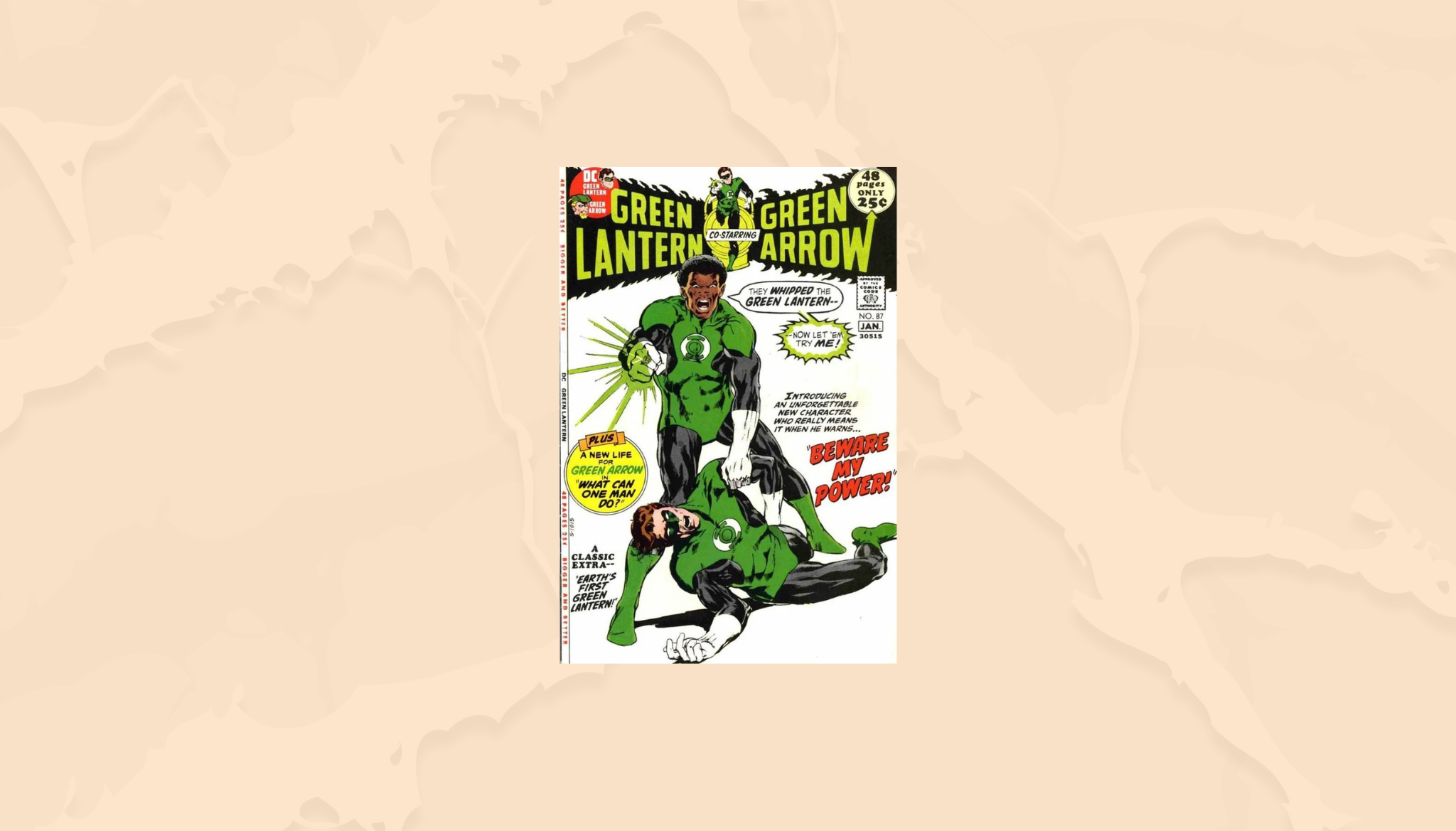

Superhero tales have always smuggled arguments about power inside four-color spectacle. In the 1960s, Marvel’s X-Men mirrored civil-rights battles; in the 1970s, Green Lantern/Green Arrow took on racism and pollution; Black Panther has spent decades interrogating colonial fallout. When critics sigh that today’s blockbusters lecture them, they might ask why previous lectures went unnoticed.

Yes, vigilante fantasies can flirt with authoritarianism, but Siegel anticipated that hazard by tethering Clark Kent to journalism. The Daily Planet’s ethics desk is his ballast, reminding readers that truth-telling is the first superpower. Gunn’s film keeps the tradition intact, foregrounding Clark’s newsroom instincts even as Metropolis explodes around him.

Déjà Vu in 2025

So why does the “woke” accusation still land? Partly because the term has become an empty catchall. Gunn’s mild assertion that Superman is “quintessentially an immigrant” inflamed cable-news panels the way Siegel’s Jewish surname inflamed Nazi censors. Never mind that Kal-El’s exile from Krypton and adoption by Kansas farmers is the most famous immigrant origin in pop culture; for some, the reminder itself feels partisan.

Meanwhile, the marketplace seems unfazed. The film’s global haul passed $272 million in its first week, with Deadline projecting steady legs through August. Critics praise its earnest tone; audiences reward it with standing ovations. If there’s a lesson, it’s that sincerity still sells—and that the loudest objections often come from people who confuse nostalgia with amnesia.

David Corenswet in Superman (2025) | Image Courtesy of IMDB

If the first people outraged by Superman were literal Nazis and the last are folks weary of “pro immigration rhetoric”, then the continuum is crystal clear. This summer’s box-office headline isn’t that Superman suddenly “went woke”; it’s that he never stopped. The S-shield was forged to shine in darkness, and darkness, alas, renews itself.

Clark Kent will keep renewing himself, too—every reboot, every generation—reintroducing a simple, radical idea: kindness is strength, and strength is accountable.