Honoring the Work that Moves Us: Inside Aimee Stevland’s Portraits of Excellence

Images courtesy Aimee Stevland

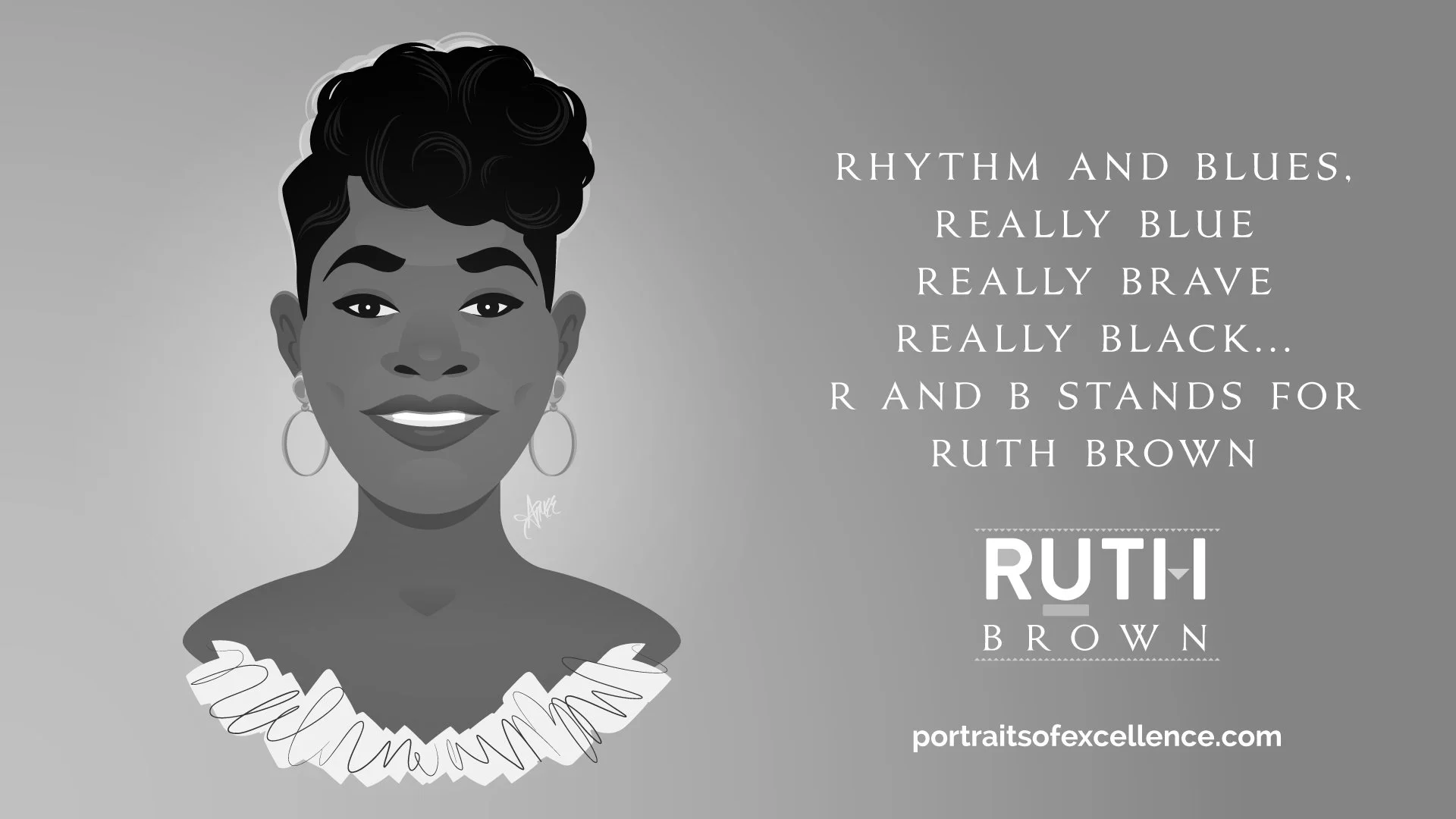

For more than 30 years, designer and illustrator Aimee Stevland has been quietly building an alternative archive of American culture—one that puts Black artists and creators back at the center of their own stories. Her series Portraits of Excellence reimagines cultural royalty through a modern lens, blending the playfulness of caricature with the dignity of classical portraiture.

In this conversation with HYVEMIND, Stevland speaks candidly about the politics of representation, the ethics of authorship as a white artist honoring Black excellence and how living with focal dystonia has redefined her relationship to creation itself.

HYVEMIND: Hi Aimee, thanks so much for your time! For readers meeting you for the first time, who are you and how did you first find your way into art and design?

Aimee Stevland: Hello! I am a designer and illustrator. Over the years, I’ve worked in different facets of entertainment, doing everything from art direction and product development to partnership marketing and environmental design.

I’d say my entry to art and design (what was called “commercial art” back then) came through the album covers in my father’s music collection. I was intrigued by how these covers could communicate so much through a single image. Of course, it also helped to grow my love of music.

I was also fascinated by the cartoons of the day. Disney, Rankin/Bass, Hanna-Barbera, Chuck Jones, Saturday morning cartoons, all the animation greats. To me, that was like stepping into a new and exciting world entirely!

HM: Do you remember the first image, moment or influence that drew you towards becoming an artist?

AS: I don’t quite remember the very first, but I do recall a couple images that really struck me as a kid.

One would be “The Sugar Shack,” a painting by artist Ernie Barnes. The image was shown during the end credits of the TV sitcom, Good Times. I was fascinated by the expressions, the elongated figures and the unbridled joy in the image. I was very happy to find it again as an album cover for Marvin Gaye’s 1976 album I Want You, since you couldn’t pause the TV back then. I’m really dating myself here, aren’t I?

I’d say the other would be the caricature art of Al Hirschfeld. I can’t remember if I first saw it in a newspaper or a library book, but the way he captured the likenesses of the celebrities of the day through simple, elegant line work was so amazing to me. I think his work is really what made me want to start drawing my own musical heroes.

HM: What or who are some of your greatest influences as a creative?

AS: Aside from all the folks I just mentioned, I think I’ve been inspired by a spectrum of artists, musicians, and designers. There are musicians like Janet Jackson and Stevie Wonder, designers like Margo Chase, Reid Miles, and Paula Scher, and artists like Norman Rockwell, Joanne Scribner, Drew Struzan, and Kara Walker. More recently, I absolutely love Kadir Nelson’s work.

HM: What first inspired Portraits of Excellence? What does this series mean to you personally?

AS: The Portraits of Excellence project came out of some personal experiences I had both in my childhood and later in my career, seeing how my musical heroes often got second class treatment when it came to artistic representation or business opportunities. When I was a kid, I first noticed it was harder to find representations of Black artists in the mainstream media, and when I did, they were often distorted or flattened, not at all a reflection of how I saw them.

As an artist who grew up near Detroit, in the shadow of Motown, the project is both a love letter to the artists that inspired me, and an act of recognition and preservation of the truth behind our American cultural history. So much of today’s popular music, style, and language, comes from Black creators. Especially now, as their voices and their history are being targeted, I feel strongly to use my talents to amplify this truth.

HM: How do you choose which cultural icons to depict, and what draws you most to their stories or presence?

AS: I’d say it’s a mix of personal influence and a desire to challenge the whitewashing and inaccuracies surrounding credited cultural significance. Some icons are deeply personal to my own experience, while others are unsung figures whose contributions have directly shaped our culture but are largely unknown.

Some have also asked why my focus has largely been on entertainment rather than activism, science, or other realms of influence, and it’s a fair question. There is a risk of reinforcing a harmful trope that the value of Black people lies only in their ability to entertain, or that one must be exceptional to deserve respect or dignity, both of which are blatantly false.

My focus on entertainment comes from both personal experience, and from the belief that these contributions are so ubiquitous to our everyday lives that they must be recognized truthfully. The project could always expand into other areas in the future.

Today’s society often elevates fame and celebrity as the only markers of cultural relevance, while at the same time undervaluing art, creativity and labor - until it profits from them. With the rapid rise of independent content creators and generative AI, I think it’s more important than ever to understand a broader history of art and commerce, the people who’ve already lived it, and the systems in which it takes place.

My hope is that by introducing thes cultural icons as an accessible entry point, I can connect today’s culture back to its originators and the stories we can learn from along the way.

HM: The portraits seem both intentional and reverent. What emotions or ideas do you hope they stir in others?

AS: The portrait style is most definitely intentional. It combines my love of cartoons and caricature with the dignity and nobility of classic Greek busts, reimagining what “cultural royalty” looks like for a modern audience. When the viral AI cartoon portrait craze hit, with everyone turning themselves into Simpsons or Ghibli characters, it reinforced what I’ve known for years. Cartoons can be playful, but they are also quite powerful when it comes to representation.

In line with that early fascination of connecting through single image, a lot of the icons are gazing back at the viewer, to spark that curiosity and joy while also inviting inspiration or reflection on the significance of their contributions.

The style also signals a significant shift to digital art, prompted by the physical limitations in my hand. These vector portraits attempt to accomplish with shape and color what Hirschfeld did so masterfully with line art.

HM: When you’re depicting Black cultural icons, how do you approach that process as someone honoring a culture?

AS: I know the optics of a white artist taking on this work can raise questions, and it should. There is a very troubling history that’s full of erasure and misrepresentation at the hands of white people. I also know in my heart this isn’t a trend or a fleeting interest. I’ve been doing this, unprompted, for 30 years already, starting as a kid, well before “DEI” became a well-intentioned corporate buzzword.

I approach this work with great care, research and responsibility because missing recognition and accurate information affects everyone. These portraits are just one small way I know how to contribute to a more accurate and affirming visual record. I’m also working on opportunities to see this project generate resources to be shared and redistributed to the communities it celebrates.

HM: What have you learned about authorship, accountability, or allyship through the making of Portraits of Excellence?

AS: I’m still figuring it out, but I’ve realized that quietly sharing the art for fun just wasn’t enough. I needed to get uncomfortable, and use whatever talent, voice, and privilege I have, to speak up louder about the inequalities I’ve witnessed and to make sure the work doesn’t reinforce the inequalities it highlights.

I also know my capacity has limits. I’m not on mainstream social media anymore so getting this art out there feels like the loudest voice I have. It’s not everything, but it’s the one thing I know how to do right now, and anything less at this point feels like complicity in maintaining a dishonest and unequal status quo.

HM: What’s your favorite portrait you’ve done for the series and why? Is there anything else about the series you’d like to share with our readers?

AS: I’m so grateful to each of these people for how they’ve enhanced our lives, so each portrait is special in its own way, but I think I may be bit partial to the Janet Jackson work that started it all.

The body of work I’ve created over the last 3 decades, inspired by her career, is quite large, and it reflects not just her artistry, but the confidence her early encouragement gave me as an artist. She was one of the first figures whose presence and creativity truly inspired me in a big way, and being able to capture and share that inspiration over the years has been incredibly meaningful, especially as her legacy begins to reclaim the recognition it was denied over the last few decades.

HM: You live with focal dystonia, can you tell us what that is? How did your diagnosis change your relationship to creativity and to your own body?

AS: Focal dystonia is a neurological movement disorder that impairs a specific task. In my case, it is the fine motor control in my drawing hand. For no apparent reason, my fingers became stiff, and my hand started to curl in on itself every time I would draw for more than a few minutes. The easiest way I can think to explain it was that through overuse, my brain had created a faulty “map” of my arm and hand, and it was causing it to react to this activity as something dangerous or harmful, which resulted in involuntary body movements and fixed hand positions.

Not only was it distressing and painful, but it also made me confront the physical limits of my body and forced me to rethink how I engage with my work. At first, it felt like a devastating loss, but over the years, I’ve learned more patience and care for my body, and my work.

HM: How do you stay connected to joy and flow when the act of creating itself sometimes asks more of you physically or emotionally?

AS: I’ve been fortunate that many of the projects I work on connect to my personal interests, which naturally makes them more fun. These days, I break projects into smaller pieces, since things take me a bit more time.

There are still many areas where I don’t feel that same “mastery” I felt like I once had, and sometimes a “happy mistake” pops up that turns into something unexpected and cool. In other areas, I feel more in control and can get fully absorbed in the flow.

I try to stay more present and maintain a flexible relationship with the creative process (music helps with that), rather than rushing straight to the end result. After all, if I’m not connecting with the work, no one else will.

HM: What has your journey as a creative and artist taught you about identity and what it means to keep showing up for your art?

AS: Try as I might, my identity will probably have some connection to being creative. But now I don’t have such a tight grasp on what that looks like anymore, literally and figuratively.

I’ve learned that when life throws you a curveball, you don’t have to give up on your dreams or goals, you just have to stay open to the idea that the journey or the result might unfold differently than you thought. Sometimes showing up simply means being willing to see where it leads next.

HM: What message would you like to share with the world—about your work, creativity, disability or beauty?

AS: I don’t know that I’m really qualified to offer any bumper-sticker wisdom, but if I had to share one thing, it might be this: embrace the mess. Value what you can do now instead of fixating on what you can’t (yet).

There are a lot of voices out there telling us to curate, polish, and perform. But I’ve found that real growth, creativity and connection doesn’t come from pretending, it comes from presence. From choosing to show up authentically, not perfectly.

Energy is too precious to spend it “faking it” so I try to spend mine on what matters most to me: showing up for myself, my art, and the people I care about. I’m not always successful, but I’ve found that’s where all that good stuff tends to find me.

Check out Aimee Stevland’s website and see more of her work: