How Mexican Artist Tuxamee Turns “Bad Taste” Into Something Sacred

Cómo el artista Tuxamee convierte bodrios en algo sagrado

Images provided by Tuxamee

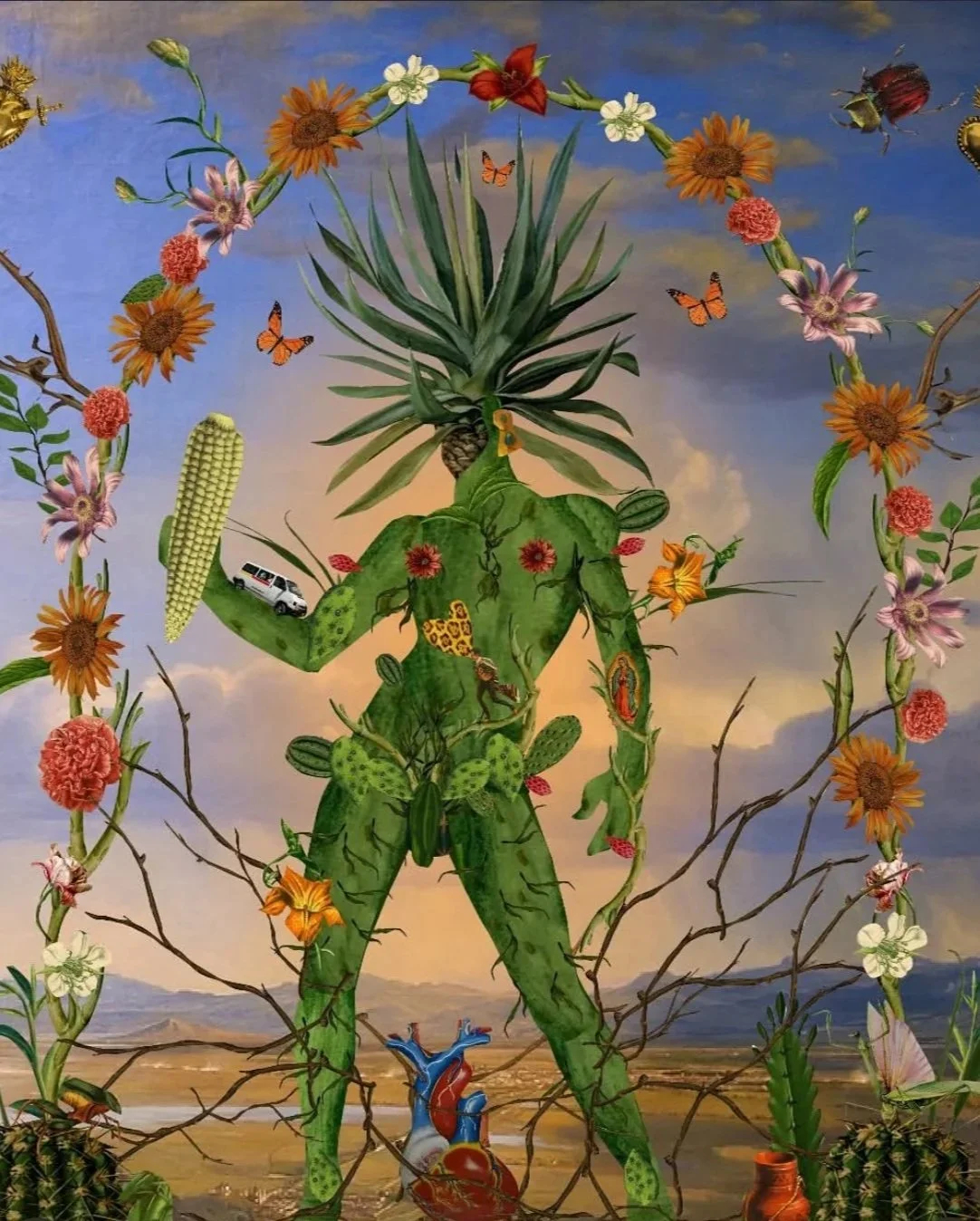

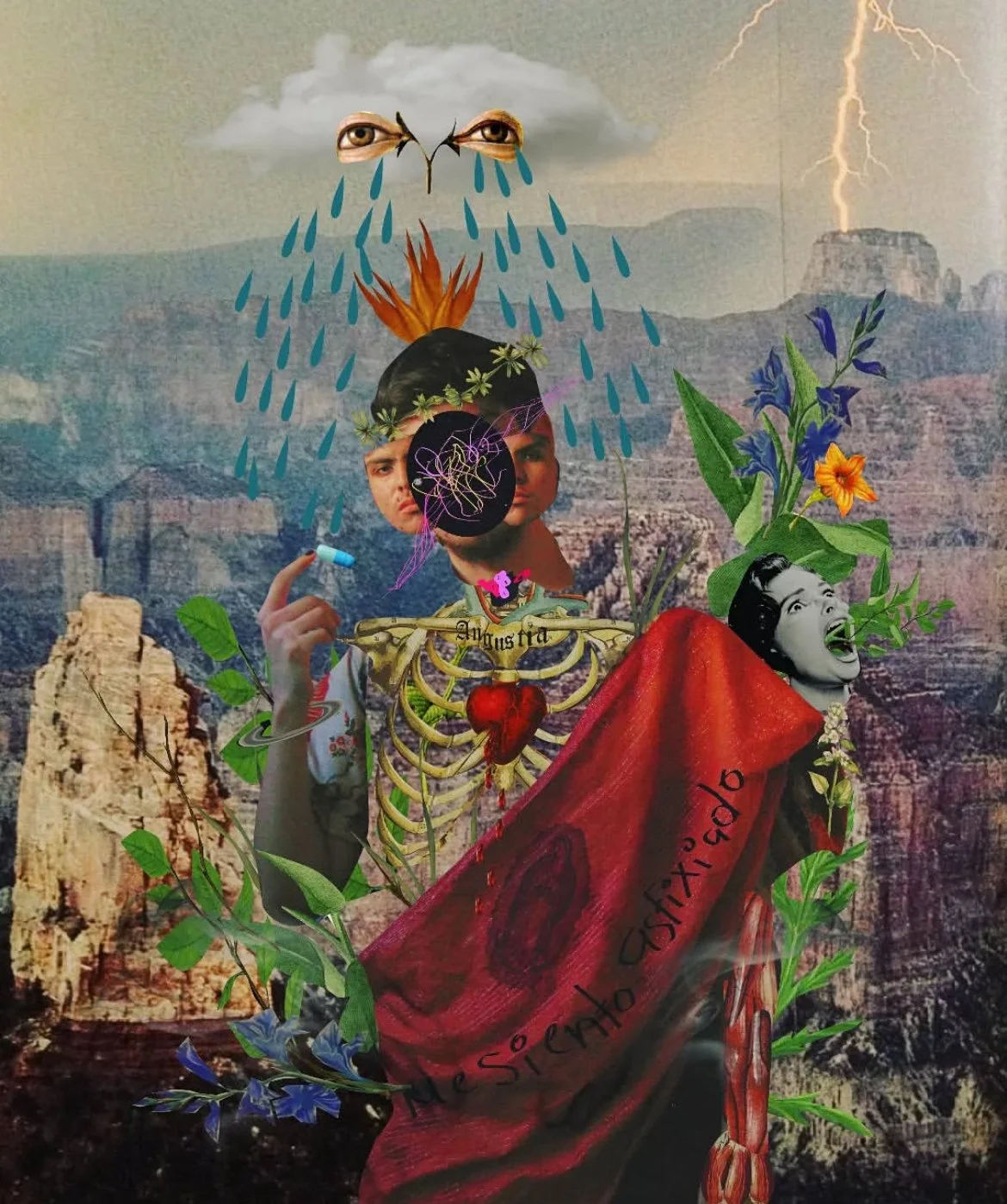

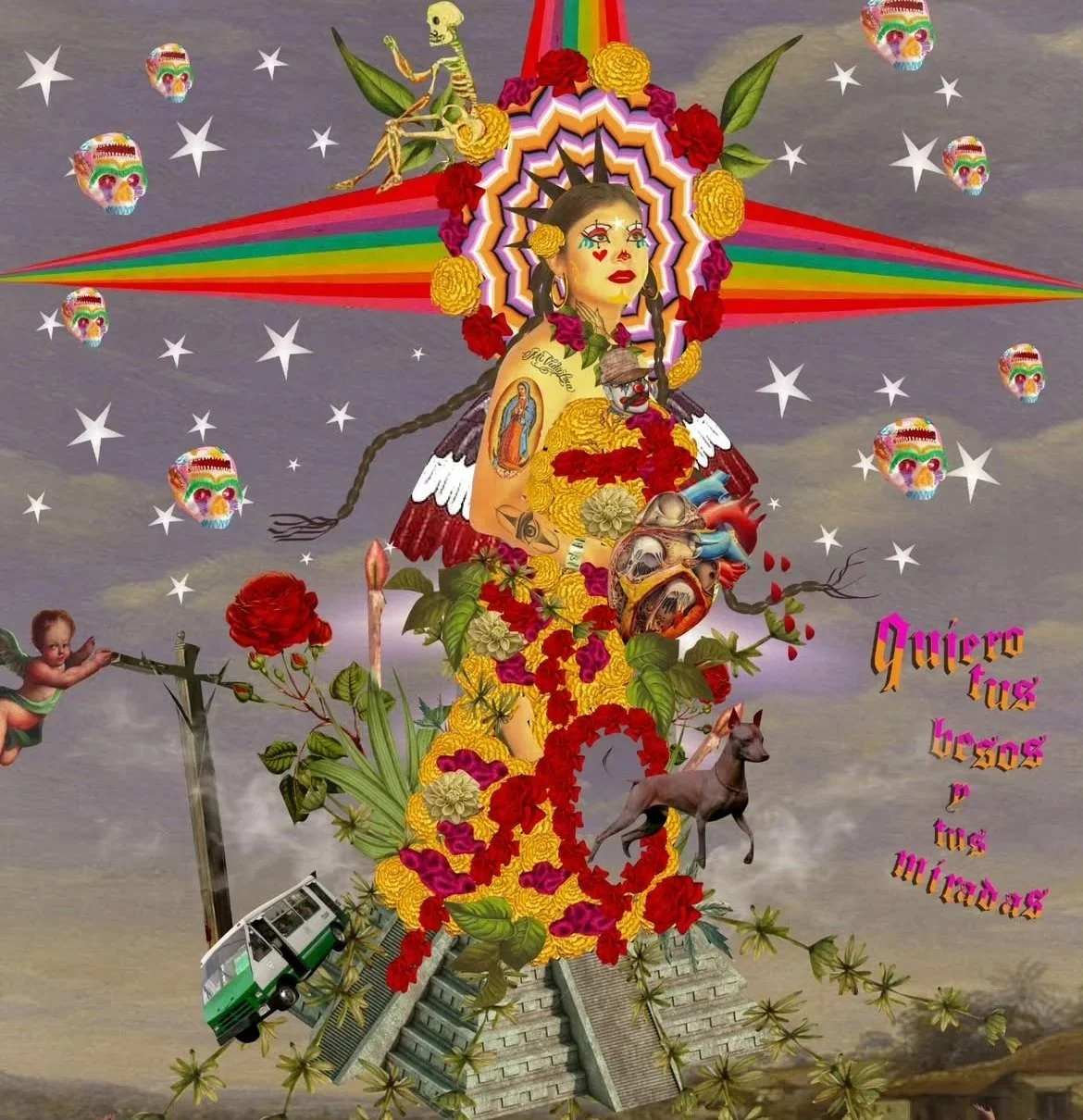

Mexican artist Irving de Jesús Segovia, better known as Tuxamee, has been constructing a visual universe where the sacred and the discarded share the same pulse.

Drawing from so-called “trash”—kitsch, barrio aesthetics, queer imagery—and merging it with Indigenous ritual, folk devotion, and the textures of life in the Bajío, he builds a cosmology that asks who gets to belong, who gets to be holy and whose memories matter.

His work elevates what others overlook, treating the humble and the humorous with the same reverence as the divine.

For Tuxamee, nothing is too small, too strange, or too “improper” to hold sacred weight. A cactus on the side of the highway, a scrap of leather from his family’s shoe shop, even the aches and repetitions of daily life—everything enters his universe as worthy of devotion.

He finds the divine in the mundane, the poetic in the discarded, the sublime in what others dismiss as ugly or bad taste. Pain, joy, boredom, ritual, graffiti, gossip, music, memory—each becomes a raw material for meaning.

In this conversation with Hyvemind, Tuxamee reflects on the inner eye that guides his imagery and how identity, devotion and the everyday traces of life gather into the universe he makes his own.

El artista mexicano Irving de Jesús Segovia, mejor conocido como Tuxamee, ha construido un universo visual donde lo sagrado y lo desechado comparten el mismo pulso.

A partir de llamar “bodrios”—lo kitsch, la estética de barrio, lo queer—y en diálogo con rituales indígenas, devoción popular y las texturas de la vida en el Bajío, levanta una cosmología que pregunta quién pertenece, quién puede ser santo y qué memorias merecen permanecer.

Su obra eleva aquello que otros pasan por alto, tratando lo humilde y lo humorístico con la misma reverencia que lo divino.

Para Tuxamee, nada es demasiado pequeño, extraño o “impropio” para ser sagrado. Un nopal al borde de la carretera, un retazo de piel del taller de zapatos de su familia, incluso los dolores y repeticiones de la vida diaria: todo entra en su universo como algo digno de devoción.

Encuentra lo divino en lo cotidiano, lo poético en lo desechado, lo sublime en aquello que otros descartan como feo o de mal gusto. El dolor, la alegría, el tedio, el ritual, el grafiti, el chisme, la música, la memoria: cada uno se convierte en materia prima para el significado.

En esta conversación con Hyvemind, Tuxamee reflexiona sobre el ojo interior que guía sus imágenes y sobre cómo la identidad, la devoción y las huellas cotidianas de la vida se reúnen en el universo que hace suyo.

HYVEMIND: To begin, tell us a bit about yourself. Who is Irving and where does your artist name Tuxamee come from? Does it have a special meaning to you?

Tuxamee: I’m someone that makes images from experience, as a form of healing and finding comfort and to observe what is happening around me and give it another perspective, whether it’s fun, serious or a blend of different worlds.

What I create mixes the cultural and geographic worlds of Guanajuato, Tlaxcala, and Puebla.

My artistic name, Tuxamee, comes from a Wixárika word I discovered as a child during a visit to Mezquitic, near San Andrés Cohamiata. I remember seeing this word written an a wall and I wrote it down in a notebook, something I used to do as a child. When I was 16, in high school, I decided to use it without any concrete intention but only because I wanted a name for Facebook. Over time, it stuck and became part of me—eventually becoming my artist name.

Tuxamee is also a type of corn—one of the most popular types of corn in Mexico. I connect it to places like Tlaxcala or San Miguel Canoa, territories where planting, tortillas and community are an essential part of life.

HYVEMIND: Para comenzar, cuéntanos un poco de quién eres tú. ¿Quién es Irving y de dónde viene el nombre Tuxamee? ¿Tiene un significado especial para ti?

Tuxamee: Soy un ser que construye imágenes desde mi experiencia, como una forma de sanarme, de cobijar, de observar lo que sucede a mi alrededor y darle otra perspectiva, ya sea divertida, seria, o una mezcla de mundos. Trabajo desde el collage, el dibujo, la vestimenta y otros medios visuales para explorar lo que siento, lo que veo y lo que vivo.

Lo que se hace, mezcla los mundos de entornos geográficos culturales de Guanajuato, Tlaxcala y Puebla.

Mi nombre artístico, Tuxamee, proviene de una palabra wixárika que encontré en mi infancia, durante una visita a Mezquitic, cerca de San Andrés Cohamiata. Recuerdo ver esa palabra escrita en una pared y anotar en una libreta, una práctica que hacía desde mi infancia. A los 16 años, en la preparatoria, decidí usarla sin una intención concreta, solo porque quería un nombre en mi facebook. Con el tiempo, se quedó, se volvió parte de mí, y terminó siendo mi nombre artístico.

Tuxamee también es un tipo de maíz, uno de los más comunes en México, lo enlazo con territorios como Tlaxcala o San Miguel Canoa, lugares donde la siembra, la tortilla y la comunidad son parte fundamental de la vida.

HM: In your IG bio it says that you make “rubbish and things that are anti-asethetic”. Can you explain what you mean?

Tuxamee: “Bodrio” (roughly translated to rubbish) is wordplay I use to describe myself. Calling something “bodrio” is commonly used with a negative connotation to talk about something ugly, absurd or made in poor taste. When I started creating, I came across diverse opinions, because this is how being a creator is: there will be those that like your work and those that don’t.

I remember the opinion of a man who came from the world of classical art. He said that art should follow certain cannons, certain body proportions and what I was creating wasn’t even close to what he described. For him, my work was a type of “bodrio”—something without aesthetics and absurd.

Instead of taking his comment as an insult, I adopted it as a declaration of my identity. I consider myself “bodriero”. I like to create from a place that doesn’t box me in, from play and from what’s popular. I work mainly with collage, but I have fun exploring other techniques and materials. For me, creating means a mix of worlds that sometimes don’t have a direct relationship or connection, but to bring them together starts to tell other stories and generate new meanings.

I’m not interested in making perfect pieces or adjusting to a canon—I’m interested in working with what’s alive, with what you can feel, with what you might cross on the path. My work is built from chaos and intuition, from the irreverent, intimate and collective. And from there I keep creating, stitching together my “bodrios” that make sense in their own environment.

HM: En tu bio dices que haces “bodrios y cosas anti/estéticas”. ¿Puedes explicar esta declaración?

Tuxamee: “Bodrio” es un juego de palabras que me gusta usar para describirme. En lo común, decir que algo es un bodrio tiene una connotación negativa, relacionada con lo feo, lo absurdo o lo de mal gusto. Cuando empecé a crear, me enfrenté a diversas opiniones, porque así es la creación: habrá a quien le guste tu trabajo y a quien no.

Recuerdo especialmente la opinión de un señor que venía del mundo del arte clásico. Él decía que el arte debía seguir ciertos cánones, ciertas proporciones corporales, y que lo que yo hacía no tenía nada que ver con eso. Para él, mi trabajo era una especie de “bodrio”, algo sin estética, absurdo.

En vez de tomar su comentario como algo ofensivo, lo adopté como una declaración identitaria. Me considero bodriero. Me gusta crear desde lo que no encaja, desde el juego, desde lo popular. Trabajo principalmente con el collage, pero me divierto explorando otras técnicas y materiales. Para mí, crear significa mezclar mundos que a veces no tienen relación aparente, pero que al juntarse comienzan a contar otras historias, a generar nuevos significados.

No me interesa hacer piezas perfectas o ajustadas a un canon; me interesa trabajar con lo que está vivo, con lo que se siente, con lo que se cruzó en el camino. Mi obra se construye desde el caos y la intuición, desde lo irreverente, lo íntimo, lo colectivo. Y desde ahí sigo creando, cosiendo mis bodrios que hacen sentido en su propio entorno.

HM: When did your love of art begin?

Tuxamee: Since childhood, my connection to art was not linear or academic, moreover it came from life experience. I grew up in León, Guanajuato, a shoemaking city. My family on my father’s side had a shoemaking business where they cut leather scraps. One of my first creative encounters was with the leather, with drawings that my dad or uncle made from me: mermaids, people, or just shapes that I played with and made stories about.

I also spent hours cutting things out of magazines: little dolls, decorations, or details I saved without knowing why—I just liked them. Even though I wasn’t allowed to play with dolls at home, I channeled this desire by creating my own kinds of dolls with books, drawings and scraps. I think that’s what began my relationship with creating, with collage and with making worlds with whatever was available, including out of what was forbidden.

Additionally, since I was very small I had a strong connection with reading. I especially remember a book called “La Verdadura Historia de la Nueva España” (The True History of New Spain). I would read it imagining everything that happened and then draw it. I started to collect magazines, biographies, prints and other other objects that, even if they seemed unrelated to art, eventually became an intimate part of my creative process. For me, each scrap and each object was a possibility.

Now as an adult, music has opened a door for me to understand my own paths. I fell in love with alternative music and its world, especially artists like Lila Downs, Lhasa de Sela and Luzmilla Carpio. The bond between music and the images I could see led me to make collages in a more conscious way, although at the beginning I wasn’t trying to make art. Everything made sense when I started studying cultural affairs management. I understood that all my lifelong practices could come together, be articulated, be found and become art that plays and tells stories.

HM: ¿Cómo empezó tu amor por el arte?

Tuxamee: Desde la infancia, mi acercamiento al arte no fue lineal ni académico; más bien, surgió de la experiencia de vida. Crecí en León, Guanajuato, una ciudad zapatera. Mi familia paterna tenía un taller de zapatos, donde recortaban retazos de piel. Ahí, uno de mis primeros acercamientos creativos fueron los recortes de piel con dibujos que me hacían mi papá o mi tío: sirenitas, personajes, formas con las que yo jugaba y me inventaba historias.

También pasaba horas recortando revistas: muñequitas, adornos, detalles que guardaba sin saber para qué, solo porque me gustaba. Aunque en casa no me dejaban jugar con muñecas, ese deseo se canalizó en crear mis propias monas con libreta, dibujos y retazos. Creo que ahí comenzó mi relación con la creación, con el collage, con hacer mundos a partir de lo disponible, incluso de lo prohibido.

Además, desde muy pequeño tuve una fuerte conexión con la lectura. Recuerdo especialmente un libro llamado La verdadera historia de la Nueva España. Leía e imaginaba todo lo que pasaba, y luego lo dibujaba. Empecé a coleccionar revistas, biografías, láminas y otros objetos, que aunque pareciera algo ajeno al arte, con el tiempo descubrí que la colección es una parte íntima de mi proceso creativo. Cada recorte, cada objeto, era una posibilidad.

Ya de adulto, la música se volvió una puerta para entender mis propios caminos. Me enamoré de la música alternativa y del mundo, especialmente de artistas como Lila Downs, Lhasa de Sela o Luzmila Carpio. Ese vínculo entre la música y la imagen me llevó a hacer collage de forma más consciente, aunque en un principio sin buscar que fuera “arte”. Todo cobró sentido cuando entré a estudiar gestión cultural. Entonces comprendí que mis prácticas, las de toda la vida, podían articularse, encontrarse y convertirse en imágenes que cuentan historias y que juegan.

HM: What themes, emotions or symbols appear over and over again in your work? What are you looking to express through your art?

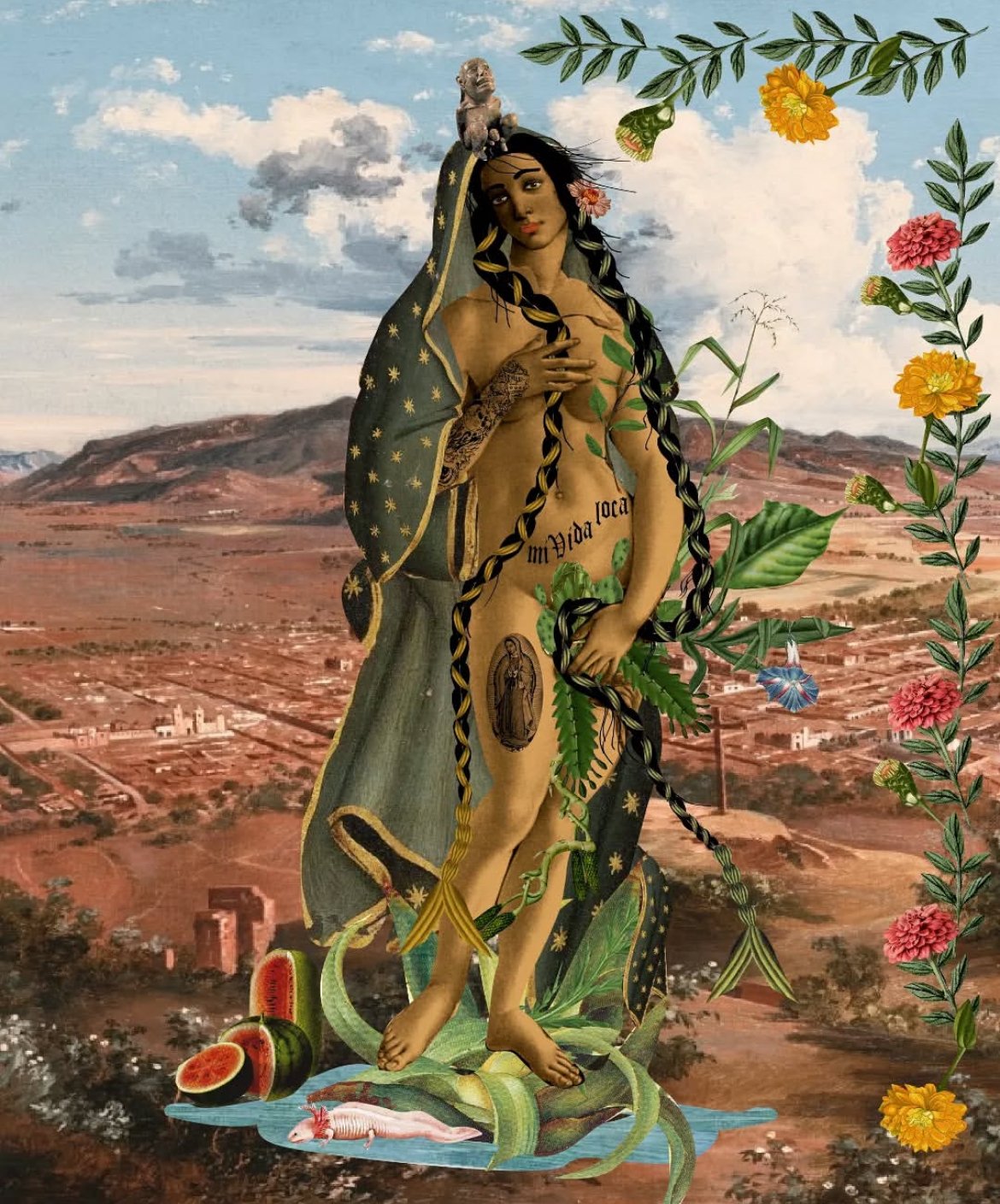

Tuxamee: My work is woven from the contexts in inhabit and the experiences that shape me. One of the central themes is the mother, the motherly energy that manifests through the Virgin of Guadalupe. It always appears in my images: in a tattoo, in a garment, in the back of a scene, sometimes it’s only hinted at, but it’s always there. For me, the Virgin of Guadalupe is more than a religious symbol: she represents origin, protection, and she is the giver of life.

Another element that reoccurs are plants that form the flora of Guanajuato—cactus, nopales, succulents. I see them on walks, in the hills, on the edges of the city and without thinking, they reappear in my work.

Devotions to Mary and other culturally significant catholic women are also fundamental to my work. I’m interested in repeating them, reinterpreting them, moving them into new places and putting them in dialogue with very different themes. And in that crossing, chicanismo appears too—that blend of the urban, the Mexican and the spirit of the border. León, where grew up and live, is a city deeply influenced by chicano culture. My work seeks to have dialogue with the graffiti that decorates the street corners: the lettering, the faces and phrases. That spirit is a part of me.

Braids are another thread running through my work—literally and symbolically. I’ve been working with this element since 2014, long before it became a trend. The braids come from my family history in San Agustín de las Flores, Silao, and from a legend tied to one of my great-great-grandmothers. They also appear in the headpieces of San Miguel Canoa, a Nahuatl-speaking community I return to again and again. Traditional dress, and the visuals and symbolism around the Nawi Xochitelpoch and the Xilona, feed my creative process.

My pieces draw from many sources: the erotic, music—especially Mexican music and cumbia, “neomexicanista” art of the 80s, the culture of the Bajío region, and the culture of La Malinche. Everything gathers itself together. In music, in nature, in everyday gestures, in the objects I find, whole universes are created.

HM: ¿Qué temas, emociones o símbolos aparecen una y otra vez en tu trabajo? ¿Qué buscas expresar a través de tu arte?

Tuxamee: Mi trabajo se teje desde los contextos que habito y las experiencias que me atraviesan. Uno de los temas centrales es la madre, la energía materna que se manifiesta a través de la Virgen de Guadalupe. Siempre aparece en mis imágenes: en un tatuaje, en una prenda, en el fondo de una escena, a veces apenas insinuada, pero siempre presente. Para mí, la Virgen de Guadalupe es más que un símbolo religioso: representa el origen, la protección, la dadora de vida.

Otro elemento recurrente son las cactáceas: cactus, nopales, suculentas, plantas que forman parte de la flora silvestre de Guanajuato. Las observo en los caminos, en los cerros, en las orillas de la ciudad, y sin pensarlo, se repiten en mi obra.

Las advocaciones marianas también son fundamentales. Me interesa repetirlas, reinterpretarlas, llevarlas a otros lugares y ponerlas en diálogo con temas muy distintos. Y en ese cruce aparece también el chicanismo: esa mezcla entre lo urbano, lo mexicano y lo fronterizo. León, donde vivo y creo, es una ciudad profundamente influenciada por lo chicano. Las esquinas están llenas de grafitis, de tipografías, de rostros y frases que dialogan con mi trabajo. Ese espíritu es parte de mí.

Las trenzas son otro hilo que atraviesa mi obra, tanto literal como simbólicamente. Desde 2014 trabajo con este elemento, mucho antes de que fuera una tendencia. Las trenzas provienen de mi historia familiar en San Agustín de las Flores, Silao, y de una leyenda ligada a una de mis tatarabuelas. También aparecen en los tocados de San Miguel Canoa comunidad nahuablante, a la que vuelvo una y otra vez en mi trabajo. La indumentaria tradicional, la investigación visual y simbólica de la Nawi Xochitelpoch y la Xilona, alimentan mi creación.

Mis piezas se nutren de múltiples ejes: lo erótico, la música—especialmente la vernácula mexicana y la cumbia—el arte neomexicanista de los 80, la cultura material del Bajío, y la zona cultural de la Malinche. Todo se va conglomerando. En la música, en la naturaleza, en los gestos cotidianos, en los objetos que encuentro, se crean universos.

HM: What cultural and personal influences inspire you?

Tuxamee: Inspiration comes from different areas and at different moments, and I think what I create depends on the era of my life. Right now, I feel that my inspiration has shifted, but the main thread always has to do with the contexts I’m living in. At the moment I'm in a place close to León in a town called Purísima de Bustos. There my inspiration is tied to altars and everything related to votive offerings. It’s something I’ve been working on for many years but am now experiencing in a different way.

Hermenegildo Bustos is an artist I’ve been revisiting a lot lately. Alongside other creators, I’ve also been spending time with the work of Julio Galán, and I’ve been thinking a lot about some artists I recently discovered called Siameses Company. I saw their work in Mexico City and I thought it was magnificent. So at this moment, I think my inspiration is undergoing a shift.

I’d also like to experiment with popular painting, but bringing it into a contemporary language, like the artist Alfredo Vilchis, whose work I saw at La Lagunilla. This context of “thank-you offerings” is something I feel very deeply and it’s a theme I want to explore more next year.

Of the many things that inspire me, I’m especially influenced by the neomexicanist movement. There are artists from that period who have shaped my vision: one is Adolfo Patiño, and another is Astrid Hadad. I find myself returning to the artists who defined Mexican art in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, revisiting their worlds and ideas. That’s the current path my inspiration is taking.

HM: ¿Qué influencias culturales y personales te inspiran?

Tuxamee: La inspiración se va dando desde diferentes áreas y en diferentes momentos, y creo que por épocas me voy moviendo de un lado a otro. Actualmente siento que la inspiración se ha transformado, pero como principal eje yo creo que tiene que ver con los contextos en los cuales voy viviendo. Actualmente estoy en un lugar que se encuentra muy cerca de León, que es un municipio llamado Purísima de Bustos. Allá mi inspiración va con los retablos, todo lo que tiene que ver con los exvotos, que es algo que he estado trabajando desde hace muchos años, pero que ahorita lo estoy palpando de otra forma distinta.

Hermenegildo Bustos ha sido también un artista que ahorita he estado rebuscando mucho. Junto a otrxs creadores en este momento ando mucho viendo también la obra de Julio Galán, dándole vuelta a unos artistas que acabo de conocer que se llaman Siameses Company. Ahí en Ciudad de México me tocó ver obra de ellos, se me hizo magnífico. Entonces en este momento creo que mi inspiración está teniendo un cambio.

Me gustaría experimentar también con el tema de la pintura popular, pero traerlo a lo contemporáneo como el artista Alfredp Vilchis, que me tocó verlo en La Lagunilla. Este contexto de los agradecimientos es un tema que traigo muy profundo y que para el siguiente año quisiera estar explorando.

En la inspiración creo que hay muchos nombres de personas, pero la corriente del neomexicanismo creo que es muy importante. Hay artistas de ese espacio que me han inspirado. Uno es Adolfo Patiño, por otro lado también está Astrid Hadad. Son artistas que ahorita estoy tratando de recordar de estos entornos del arte en México de los años 70, 80 y 90. Entonces, pues por ahí va.

HM: How has your style evolved over time? What are you interested in exploring now that perhaps you weren’t interested in before?

Tuxamee: My way of creating has transformed with time. But my work is always identifiable through my aesthetic. I call it “mi chamba”. Although the work that I did in 2015, 2016 or 2017 is very different from what I make now, the change has happened more in essence than in appearance.

At the beginning, when I was a student, I had different interests and experiences. I was more impulsive, more experimental and more anxious. I would take elements from many places without questioning much. I only wanted to experience what I was feeling, what I was seeing, and what I knew at the time. My work had a more abstract explosive tone. I was interested in Mexican textiles, people like Julio de Haro and completely digital collage—there was an almost urgent energy in my process.

Now, with everything I’ve lived and the shifts in my environment, my process has become more reflective, more intentional. I give myself time to think about what I want to say and how I want to say it. I’m still speaking about myself, about what I feel, but now I weave those emotions with sounds, with the sensations of night, with the rhythm of cumbia, with the memories gathered along the road. Everything comes together.

I’m in a phase of expansion. Lately, I’ve been drawn to experimenting with painting. I’ve been easing into it through drawing—taking classes, exploring techniques I hadn’t really touched before. I want to bring the everyday into my work, to observe what’s happening around me and transform it. That’s where I am now: thinking, practicing and opening new doors within the same universe.

HM: ¿Cómo ha evolucionado tu estilo a lo largo del tiempo? ¿Qué te interesa explorar ahora que quizás antes no?

Tuxamee: Mi forma de crear ha ido transformándose con el tiempo. Sí, mi estilo se reconoce, hay una línea estética que se identifica como “mi chamba”, aunque la obra que hacía en 2015, 2016 o 2017 es muy distinta a lo que hago ahora. El cambio ha ocurrido más en el fondo que en el exterior.

Al principio, cuando era estudiante, mis intereses y experiencias eran otras. Era más impulsivo, más experimental, más ansioso también. Tomaba elementos de muchos lugares sin cuestionarlo mucho. Solo quería expresar lo que estaba sintiendo, lo que veía, lo que no conocía. Mi obra tenía un tono más abstracto y explosivo. Me interesaban los textiles mexicanos, personajes como Julio de Haro y los collages totalmente digitales, había una energía casi urgente en mi proceso.

Ahora, con todo lo que he vivido y los cambios de entorno, mi proceso se ha vuelto más reflexivo, más consciente. Me doy tiempo para pensar lo que quiero decir y cómo quiero decirlo. Sigo hablando de mí, de lo que siento, pero también tejo esas emociones con sonidos, con sensaciones de la noche, con el ritmo de la cumbia, con las memorias del camino. Todo se va juntando.

Y estoy en una etapa de expansión. Últimamente me interesa experimentar con la pintura. Me he estado acercando desde el dibujo, tomando algunas clases, asomándome a técnicas que no había explorado del todo. Quiero traer lo ordinario a mi trabajo, mirar lo que pasa alrededor y transformarlo. Estoy en ese movimiento, pensando y practicando, abriendo nuevas puertas dentro del mismo universo.

HM: Is there a piece you consider a turning point in your career or personal development? Tell us the story behind it.

Tuxamee: There are several works that have been important in my artistic growth, but one in particular really left its mark. It opened doors, reshaped my perspective and made me rethink my entire practice. That piece is “El Nacimiento de la Lupe”, created in 2021, with the support and insight of art historian Juanki Buenrostro.

The piece went through a long process—about a year and a half. I first made it under the title “La Venus Mazahua”, but something didn’t sit right. I felt it wasn’t fully aligned or responsible, like it was missing truth or history. That’s when I started rethinking what I wanted that Venus to be.

At the time, I was researching the indios broncos, a traditional dance from León, Guanajuato, and along the way I came across the story of La Pájara, a trans woman who talked about imagining her body as a Venus. Everything she said stuck with me. I wrote things down, sketched, imagined—and little by little, those ideas turned into “El Nacimiento de la Lupe”.

The piece is about rebirth, a kind of restarting. You see a Venus covered in braids, tattooed like a chola, wrapped in the cloak of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Above her, a Coatlicue figure gives birth. Below, an axolotl, an animal known for being able to regenerate limbs, signals new life. There are watermelons too, a nod to Frida Kahlo’s “Viva la Vida”— a celebration of what’s coming next, of what’s being born.

The piece didn’t stay just as an image. With Juanki’s help, it turned into a research project. And later it became a performance: the drag queen Matraka, dressed as the Virgin of Guadalupe, shed her cloak in the Jesús Gallardo Gallery while the audience pinned tiny charms made from nota roja newspaper onto her. It felt like a celebration, a living text—a transfemme Virgin.

Without a doubt, this piece opened many doors for me. It’s one of my favorites because it showed me that a single image can branch out into many different paths.

HM: ¿Hay alguna pieza que consideres un punto de inflexión en tu carrera o en tu desarrollo personal? Cuéntanos la historia detrás de ella.

Tuxamee: Hay varias piezas que han sido fundamentales en mi desarrollo artístico, pero hay una en particular que me marcó, que me abrió puertas y me hizo repensar todo mi trabajo. Esa pieza es "El Nacimiento de la Lupe", y surgió en 2021, gracias también a la mirada y acompañamiento lx historiadorx de arte Juanki Buenrostro.

La pieza pasó por un proceso largo, como de un año y medio. Primero la había hecho y titulado La Venus Mazahua, pero algo no me convencía. Sentí que no estaba muy "correcta", muy responsable, como si le faltara verdad o historia. Y fue ahí donde empecé a repensar cómo quería que fuera esa Venus.

En ese momento estaba investigando sobre los indios broncos, una danza tradicional de León, Guanajuato, y en ese camino conocí la historia de La Pájara, una chica trans que hablaba de cómo imaginaba su cuerpo como una Venus. Todo lo que decía me llegó a la cabeza. Lo fui anotando, dibujando, imaginando, y poco a poco esa idea se transformó en El Nacimiento de la Lupe.

La pieza es un renacimiento, un reinicio. En la imagen se ve una Venus con trenzas que cubren su cuerpo, tatuada como una chola, con un manto de la Virgen de Guadalupe. Arriba, una Coatlicue da a luz. Abajo, un ajolote, esa criatura que se regenera, anuncia una nueva vida. Y también están las sandías, un guiño a Viva la Vida de Frida Kahlo, como una celebración a lo que sigue, a lo que nace.

Esta pieza no solo fue la imagen. También se convirtió en investigación, gracias a Juanki. Y después en performance, cuando una drag queen “Matraka” vestida como Virgen de Guadalupe— se desprendía de su manto en la Galería Jesús Gallardo, mientras el público le colocaba milagritos hechos con nota roja del periódico. Era una fiesta, una escritura viva, una Virgen travesti.

Sin duda, esta pieza me abrió muchas puertas y es una de mis obras favoritas porque me enseñó que de una imagen pueden nacer muchos caminos.

HM: How does your art engage with the community or the territory you come from? What role does identity play in your creative process?

Tuxamee: For me, art is a form of close conversation. I like staying connected to the environments I inhabit, and I feel my work is nourished by that constant movement. I don’t like staying fixed in one place; I move in seasons, I shift, I travel through spaces and let those spaces travel through me. That’s who I am. That’s my spirit: exploratory, restless, curious—even when things get hard. Because it’s not all simple; there are difficult moments and complicated situations that are also part of my story and become material for creation.

One of the places that has shaped me most is the community of San Miguel Canoa (Puebla) and Tlaxcala, where almost ten years ago I began collaborating with the cuadrilla de carnival Nawi Xochitelpoch, a collective of huehues and Xilonas led by women from the Indigenous Canoa community. There, Maestra Guadalupe Arce welcomed me into a world that became a deep, intimate, and transformative part of my life. Thanks to her, to Quitzel Arce, and to the entire community, I’ve felt embraced—like part of a family. Many of my pieces draw from that experience: works inspired by cacahuazintle corn, by the novias de carnival and by the rhythms and colors that live only there

Guanajuato, especially León, is where I was born, and it’s a core part of my memory. Living between Silao, León, and now Purísima has given me a grounded sense of the region’s cultural life, especially on the outskirts. I’ve lived in neighborhoods like Las Joyas and El Coecillo, where cumbia, sonidero, and chicano influence shape the streets, but where you can also feel the tension and the weight of violence. I’ve witnessed hard moments that leave a mark, yet all of that becomes creative material. Those contrasts are where the need to heal emerges—where the impulse to create and process what we live takes shape.

My work comes from that mix of affections and territories, because it’s not just about naming what happens, but transforming it—telling it in another way.

HM: ¿Cómo dialoga tu arte con la comunidad o el territorio del que vienes? ¿Qué papel juega la identidad en tu proceso creativo?

Tuxamee: Para mí, el arte es una forma de diálogo cercano. Me gusta estar en contacto con los entornos que habito, y siento que mi trabajo se alimenta de ese movimiento constante. No me gusta estar fijo en un solo lugar; más bien, voy por temporadas, me muevo, atravieso espacios, me dejo atravesar por ellos. Así soy, así es mi espíritu: explorador, inquieto, curioso, incluso en lo difícil. Porque no todo es color de rosa; hay momentos duros, situaciones complicadas que también forman parte de mi historia y se convierten en ejercicio de creación.

Uno de los entornos que más me ha marcado es la comunidad de San Miguel Canoa (Puebla) y Tlaxcala, donde hace casi diez años comencé a colaborar con la cuadrilla de carnaval Nawi Xochitelpoch, un colectivo de huehues y Xilonas liderado por mujeres de la comunidad indígena de Canoa. Allí conocí a la maestra Guadalupe Arce, quien me abrió las puertas de ese mundo y con quien he creado una conexión profunda, íntima y transformadora. Gracias a ella, a Quitzel Arce y a la comunidad, me he sentido arropado, parte de una familia. De esa experiencia han surgido obras inspiradas en el maíz cacahuazintle, en las novias del carnaval, en los ritmos y colores que solo se viven allá.

Por otra parte, Guanajuato y en especial León es donde nací. Es el lugar de mi nacimiento y parte esencial de mi memoria. Vivir entre Silao, León y ahora Purísima me ha dado una perspectiva muy consciente del movimiento cultural de la región, sobre todo en las periferias. He vivido en colonias como Las Joyas y barrios como El Coecillo, donde se respira cumbia, sonidero, la influencia del chicanismo en el Bajío, pero también se sienten las tensiones y el peso de la violencia. He visto situaciones difíciles que marcan el camino, pero todo eso también se transforma en herramientas creativas. Es en estos contrastes donde nace la necesidad de sanar, de hacer obra, de pensar cómo podemos procesar lo que vivimos.

Mi trabajo surge de ahí, de esa mezcla de afectos, territorios,porque no solo se trata de nombrar lo que pasa, sino de transformarlo, de contarlo de otra manera.

HM: Many artists talk about art as a form of resistance or reconnection. What does it mean for you to create in this moment, historically and socially?

Tuxamee: Right now, talking about what it means to be Mexican is complicated. The idea of “love of country” is often used in a shallow, chauvinistic way—repeated like a slogan without any reflection on its deeper implications. Still, it’s a subject I’ve worked with for years. It’s tied to political movements and nationalist constructions that have shaped our history, and I like bending those narratives, giving them new meaning. The word “nationalism”, after all, carries consequences.

So when I approach these themes now, I don’t want to speak only from resistance—though resistance is part of the political structure. I want to speak from lived experience: to tell what’s happening through life itself, almost like inner-eye chronicles. And that’s hard, because we’re living through moments that echo past cycles of violence. What’s happening in Guanajuato, Tlaxcala, Puebla—it’s part of daily life. It cuts through everyone’s experience.

In that context, creating becomes a lens—a way to numb or ease the pain, to forget or remember, to process the mental turbulence of what’s happening. At the same time, it’s a tool to reshape those experiences. Creating is how I carry and release what I see and feel. It’s my way of finding another way to live within the reality we face every day.

Art often gets framed as something that must be political or ideological. And yes, creativity inevitably carries political weight. But for me, it’s about naming what’s happening—calling it out, pulling it from the body and mind, turning it into something visible that can breathe on its own. Otherwise, it stays lodged inside.

So now I see the political in my work not as something explicit, but as an intimate chronicle of the present—a way of observing and transforming the world through that inner eye, giving it shape and releasing it outward.

HM: Muchos artistas hablan del arte como una forma de resistencia o de re-conexión. ¿Qué significa para ti crear en este momento histórico y social?

Tuxamee: En este momento, hablar del ser mexicano se ha vuelto muy complejo. Hoy se utiliza mucho esa idea de amor a la patria, pero desde un sentido muy chovinista, casi como una consigna repetida, sin detenerse en las implicaciones profundas que tiene. Y, sin embargo, es un trabajo que llevo haciendo desde hace mucho tiempo. Porque también tiene que ver con movimientos políticos, con construcciones nacionalistas que han marcado nuestra historia, me gusta torcerlas, darles otro sentido y esa palabra “nacionalismo” no viene sin consecuencias.

Por eso ahora, cuando pienso en estos temas, ya no quiero abordarlos únicamente desde el resistir—aunque claro que ahí hay una estructura política— sino desde otro espacio. No me interesa tanto darles una connotación cercana a algo específico, sino hablar desde lo que se vive: contar lo que sucede con la vida misma como si fueran crónicas del ojo interior. Y no es fácil, porque estamos en un punto donde muchas de las situaciones se están repitiendo históricamente. Los entornos de violencia, la guerra dolosa, lo que se vive en Guanajuato, en Tlaxcala, en Puebla… es parte del día a día. Está ahí, cruzando vidas.

Entonces, frente a eso, crear se convierte en una especie de lente, que te anestesia, que te calma el dolor, que te permite a veces olvidarte o acordarte, sentir una turbina mental por lo que está pasando. Y al mismo tiempo, es una herramienta para darle otro sentido a todo eso. Crear es mi manera de cargar y descargar todo lo que veo y siento. Es buscar otra forma de vivir dentro de lo que nos toca ver a diario.

Siento que muchas veces se le impone al arte un enfoque político/ideológico, y sí, inevitablemente hay una implicación política en lo creativo. Más bien está en mí nombrar lo que se está viviendo, denunciarlo, sacarlo del cuerpo y la mente, convertirlo en algo visible que respire por su cuenta. Porque si no, se queda ahí enquistado.

Entonces ahora entiendo lo político en mi obra no como un acto explícito, sino como una crónica íntima del presente. Una manera de observar y transformar el universo desde ese ojo que llevo dentro, darle sentido y sacarlo al mundo.

HM: Do you have a favorite piece? What is it, and why?

Tuxamee: I have several pieces that feel meaningful to me, but lately one in particular stays close: an exvoto I made for El Niño Cieguito, as a way of giving thanks for the miracles I experienced in Puebla. Even though it’s full of religious symbolism, it also captures the beauty of the festivals in Puebla and Tlaxcala.

El Niño Cieguito is an important devotional figure in Puebla, especially in the capital, where he’s celebrated in August. In my piece, he holds a little taquito de carne árabe in one hand, and on his lap rests a festival bread from San Juan Huactzinco in Tlaxcala. He’s surrounded by an arch of poblanos covered in nogada, with Capuchin nuns standing guard. With this image, I wanted to create a visual chronicle of the celebration—mixing the religious with the everyday: the smells, the flavors, the walking, the devotion.

What I love most about this piece is that it works as an exvoto rooted in both tradition and my own life. I’m a devotee of El Niño Cieguito and have gone to give thanks multiple times. In this piece, I gave him my own eyes. I asked myself: What would it mean to offer my eyes as a gesture of gratitude? So the Niño keeps my eyes, and I feel a little closer to his miraculous gaze.

The original figure of El Niño is striking: he has empty, bleeding sockets, and carries his eyes reflected in a mirror. It’s raw and deeply moving—about walking without seeing, believing without looking. My piece gathers all those elements—eyes, blood, the taco, the bread, the nuns, the chiles—into a kind of synthesis of celebration, faith, and memory. And even though it can be interpreted in many ways, for me it’s profoundly intimate. Every time I look at it, I think: Wow, I really love this piece. It feels alive, like a small hug that holds you even in difficult times.

HM: ¿Tienes alguna pieza favorita tuya? ¿Cuál es y por qué?

Tuxamee: Hay varias piezas que considero significativas, pero últimamente hay una que me tiene muy presente: un exvoto que le hice al Niño Cieguito, como agradecimiento por los milagros de estar en Puebla. Es una imagen que, aunque está llena de simbolismos religiosos, también contiene una belleza profunda sobre lo que son las fiestas en Puebla y Tlaxcala.

El Niño Cieguito es una figura muy importante dentro de la devoción poblana, sobre todo en la capital, donde se celebra en agosto. En mi pieza, lleva en una mano un taquito de carne árabe y en su falda descansa un pan de fiesta de San Juan Huactzinco, en Tlaxcala. Lo rodea un arco de chiles poblanos bañados en nogada y unas monjas capuchinas lo resguardan. Quise crear con esta imagen una crónica visual de la fiesta, mezclando lo religioso con lo cotidiano, con lo que se vive realmente: los olores, los sabores, las caminatas, la devoción.

Algo que me encanta de esta pieza es que la considero un exvoto que dialoga tanto con la tradición como con mi vida. Yo soy ferviente del Niño Cieguito y le he ido a agradecer varias veces, y en esta pieza le puse mis propios ojos. Me pregunté: ¿qué pasaría si le entrego mis ojos como símbolo de gratitud? Entonces, el Niño se quedó con mis ojos, y yo quedé un poco más cerca de su mirada milagrosa.

Es impresionante la figura original del Niño: no tiene ojos en sus cuencas, las cuales sangran, y carga sus ojos en un espejo en la mano. Es una imagen cruda y, al mismo tiempo, profundamente conmovedora. Habla de caminar sin ver, de creer sin mirar. Esta pieza, con todos esos símbolos los ojos, la sangre, el taquito, el pan, las monjas y los chiles, terminó siendo una síntesis de las fiestas, de la fe, de la memoria. Y aunque tiene muchas lecturas posibles, para mí es profundamente íntima. Cada vez que la veo, digo: "wow, esta pieza me encanta". Se siente viva, como un abrazo que sostiene incluso en tiempos difíciles.

HM: How do you balance the spiritual, the political and the personal in your work?

Tuxamee: For me, creating is building a world of my own. I don’t see my work as an isolated object but as a constellation of experiences, memories, readings, encounters, and obsessions that weave together almost on their own. It’s an experimental practice that comes from the body, identity, and personal history, but also from research, imagination, and intuition. I’m not always looking for a clear logic—images, ideas, and symbols appear without connection at first, and over time they reveal an intimate thread. They’re fragments of myself that, once shared, become an open narrative for others.

Lately I’ve been reading Victoria Cirlot, who writes about inner vision in the work of Hildegard von Bingen—a medieval mystic who has accompanied me for years. What moves me about Hildegard is her ability to create images that don’t depict an external reality but her own intuitive world. Cirlot’s idea of the “inner eye” has helped me see my practice as an inward work—drawing from what runs in the blood, what sparks the neurons, what ripens in silence. For me, creation is about making the invisible parts of my life visible.

People read my work in different ways: sometimes as contemporary art, sometimes as folk art, sometimes as something uncategorizable. Sometimes they don’t call me an artist at all. And honestly, that doesn’t bother me. I’m not trying to fit into a movement or claim a specific lineage. I think of myself as someone who can inhabit many spaces without fully belonging to any of them. I prefer not to limit myself and let the work appear as a living organism.

I deeply believe that art is a form of freedom—a way to question yourself and answer yourself at the same time. A way to bring order without following rules others created. A way to say: here I am, this is who I am and this is what gives me life.

HM: ¿Cómo equilibras lo espiritual, lo político y lo personal dentro de tu obra?

Tuxamee: Para mí, crear es construir un mundo propio. No pienso en la obra como un objeto aislado, sino como una constelación de experiencias, recuerdos, lecturas, encuentros y obsesiones que se entretejen casi sin darse cuenta. Es un ejercicio experimental que nace del cuerpo, de la identidad, de la historia personal, y también de lo que se investiga, se conoce, se imagina. A veces ni siquiera busco una lógica evidente: simplemente dejo que aparezcan imágenes, ideas y símbolos que al principio no tienen conexión, pero que con el tiempo revelan una trama íntima. Son fragmentos de mí, que al compartirse, se vuelven una narrativa abierta hacia el mundo.

Últimamente he estado leyendo mucho a Victoria Cirlot, una académica que trabaja sobre la visión interior en la obra de Hildegard von Bingen, una mística medieval que me acompaña desde hace muchos años. Lo que me conmueve profundamente de Hildegard es su capacidad de construir imágenes que no representan una realidad exterior, sino su propio mundo intuitivo. La idea de "ojo interior" que Cirlot desarrolla me ha inspirado a entender la práctica como esa labor interior que se va dibujando a partir de lo que corre por la sangre, lo que articula las neuronas, lo que maduran los silencios. La creación, para mí, tiene más que ver con hacer visible lo invisible de lo que vivo.

A veces me dicen que mi trabajo es arte contemporáneo, a veces lo leen desde el arte popular, otras veces lo consideran fuera de categoría. A veces ni siquiera me nombran artista. Y la verdad, no me preocupa. No busco encajar en un movimiento o encontrar a qué corriente pertenezco. Me pienso como alguien que puede habitar todos los espacios sin pertenecer del todo a ninguno. Prefiero no limitarme y permitir que la obra aparezca como un organismo vivo.

Creo profundamente que el arte es una forma de libertad. Una forma de cuestionarte y contestarte al mismo tiempo. Una forma de darle un orden, sin tener que obedecer las reglas que otros establecieron. Es una forma de decir: aquí estoy, esto soy y esto me da vida.

HM: What are you dreaming of making in the coming years? How do you imagine the impact you want to leave?

Tuxamee: The truth is, I don’t think too much about the act of creating or about constantly seeking something new. I just let myself be carried by the process. Some themes shift over time and others stay—already rooted in my work without me chasing them. Sometimes ideas scare me, but I don’t dwell on that, because there’s also the practical side of being an artist: making a living, treating this as a profession, a craft that requires discipline and structure. So instead of focusing on innovation, I focus on how to sustain this space through what I love—through observation and wonder. What excites me is feeling that something resonates, moves me, or makes me question things—and that impulse is what drives me to create.

I no longer think of series the way I used to. What matters now is that whatever I make connects with what I’m living, even when it’s a commission.

In the future, I want to keep exploring music-related work. I love creating album covers and visual languages that accompany sound—images that speak to the lyrics, the rhythm, the atmosphere. I also want to develop more performative work with Trenza, this character rooted in something very intimate but still full of potential to grow into a more theatrical space. I’d like to explore Teatro de Carpa in my own way—those worlds that mix humor, melodrama, and critique, like María Conesa or Lucha Reyes. I think a lot about the Teatro Blanquita, about regional music and about the way it was performed.

I’m still at the beginning, still experimenting, but I feel the path is leading me toward something more theatrical. And even if I’m not seeking innovation outright, deep down what I want is to surprise myself—start again from what feels alive, and keep weaving together worlds that may not always follow a clear logic, but hold together through emotion and desire.

HM: ¿Qué sueñas construir con tu arte en los próximos años? ¿Cómo imaginas el impacto que quieres dejar?

Tuxamee: La verdad es que no pienso tanto en el acto de crear, ni en estar buscando lo nuevo. Simplemente me dejo llevar. Hay temas que van mutando y otros que son constantes, que ya están instalados en mi trabajo sin que los busque. A veces hay ideas que me dan miedo, pero no me detengo en eso porque también existe el otro lado de ser artista: la subsistencia, asumir esto como una profesión, un oficio que también exige disciplina y estructura. Entonces, más que pensar en innovar, pienso en cómo sostener este espacio desde lo que me gusta, desde la observación, desde el asombro. Lo que me emociona es sentir que algo me vibra, que me conmueve, que me hace preguntarme cosas, y ese mismo impulso es el que me mueve a crear.

Ya no pienso tanto en series como antes. Ahora lo que me interesa es que lo que hago se conecte con lo que estoy viviendo, aunque a veces se trate de una comisión.

En el futuro quiero seguir explorando más el campo musical. Me gusta mucho trabajar en portadas de discos, en lenguajes visuales que acompañan el sonido, que dialogan con una letra, con un ritmo. También quiero avanzar en lo performativo con Trenza, este personaje que emerge desde una raíz muy íntima, pero que todavía siento que puede expandirse hacia un territorio más escénico. Me gustaría explorar el Teatro de Carpa al modo Tuxamee, esos mundos donde se conjugan la risa, el melodrama y la crítica, como lo hacían María Conesa, Lucha Reyes, pienso mucho en el Teatro Blanquita, en la música vernácula, en cómo se interpretaba.

Aún estoy en un inicio, en una etapa de tanteo, pero siento que por ahí va. Que el camino me está llevando hacia una creación más escénica. Y aunque no piense en innovación, en el fondo lo que busco es sorprenderme a mí mismo, recomenzar desde lo que siento vivo, y seguir entretejiendo mundos que, aunque a veces no tengan lógica aparente, se sostienen desde la emoción y el deseo.

HM: What advice would you give to new generations of artists who want to honor their culture while still experimenting?

Tuxamee: What I always recommend to people starting out in the creative field is this: don’t stop sharing your work. Being afraid to show what you make is really just denying yourself opportunities. And yes, it might sound practical, but it’s true—those of us who live off our art need chambitas. We need small jobs and ways to sustain ourselves through our creativity.

So the most important thing is to share. Share what you make, who you are, what moves you. Keep showing up—because sharing is also a mental, emotional, and creative practice. Sometimes things won’t turn out the way you expect, but other times they’ll be better than anything you imagined, even in places you never thought possible.

That’s why I think the point isn’t to limit yourself, but to erase those limits and connect who you are with the world. Everyone has their own personality and creation has no rules.

So my advice is: share your work, build relationships with the people around you, take in feedback and offer what you have to give—from your imagination outward.

HM: ¿Qué consejo le darías a las nuevas generaciones de artistas que buscan honrar su cultura sin dejar de experimentar?

Tuxamee: Creo que lo que más voy a recomendar siempre a las personas que están empezando dentro del ámbito creativo es que no dejen de compartir su trabajo. Tenerle miedo a mostrar lo que hacemos es, en realidad, no permitirnos tener trabajo. Y sí, sé que puede sonar superficial, pero algo muy importante para quienes nos dedicamos al arte es tener chambitas: poder sostenernos de esto que hacemos, vivir de nuestra creatividad.

Entonces, lo realmente importante es compartir. Compartir lo que haces, lo que eres, lo que te mueve. Y darle, y darle, y darle… porque también es un ejercicio mental, emocional y creativo. A veces las cosas no salen como uno espera, pero otras veces resultan aún mejor de lo que imaginábamos, incluso en terrenos que ni habíamos considerado posibles.

Por eso, creo que no se trata de limitarse, sino de borrar esos límites y conectar lo que somos con el mundo. Porque cada quien tiene una personalidad distinta, y la creación no tiene reglas.

Así que mi consejo es: comparte lo que haces, crea vínculos con las personas que te rodean, retroalimenta y reparte lo que tienes para dar desde tu imaginación.

Follow/sigue Tuxamee on Instagram.