From Banking to Breadcrumbs: Kevin Howard on Finding Clarity in a Complicated System

One Banker’s Effort to Turn a Lifetime Inside Finance Into Insight, Guidance and a Clearer Picture for Those Who Follow

On a Friday afternoon in 2008, Kevin Howard boarded a flight believing his job was safe.

It was the height of the Great Recession and executives at Wachovia, the financial institution where Howard worked, had just reassured the commercial banking team that the bank would hold.

And while the mortgage division was under pressure, Howard’s side of the business—lending to manufacturers, clinics and small companies—remained steady. So, Howard left the meeting with a legal pad of Monday calls to make and flew back to Phoenix expecting a normal week.

When the plane landed, his phone lit up. The bank had been sold. First to Citigroup. Then, days later, that deal collapsed and Wells Fargo stepped in.

“All weekend we studied the financials,” Howard told Hyvemind during a recent interview. “We had to talk customers off the ledge. If they panic, the whole thing unravels.”

On Monday he reassured them. By Thursday, the reassurances sounded hollow and customers stopped returning calls. Within months, most of Wachovia’s Western bankers were laid off. Howard, who had spent nearly 30 years in commercial lending, was among them.

For someone who says—without irony—that he grew up wanting to be a banker, the loss felt personal.

“I really loved the work,” he said. “I wanted to help entrepreneurs grow their businesses. That’s what I thought banking was for.

The next several years were unstable. Like many professionals displaced during the recession, he discovered that the labor market had limited patience for middle-aged specialists whose experience was tied to institutions that no longer existed.

It took seven years before he made it back into commercial banking, this time at U.S. Bank.

By most measures, it looked like a recovery. The title was back, the paycheck stabilized and his routine returned. He was once again sitting across from business owners, structuring loans, reviewing financial statements and doing the work he had trained for his entire adult life.

Then, one morning, something changed.

Howard, now 60, told Hyvemind he remembers waking up before his alarm and lying there, staring at the ceiling, already tired.

“I remember thinking, is this really it?” he said.

He described the feeling carefully, as if wary of overstating it. He didn’t hate the job, and he wasn’t burned out. He saw the path clearly, but what he couldn’t see was the meaning.

“It scared me,” he said. “It felt like the next 30 years were already decided, and I couldn’t figure out what it was for.”

That thought followed him to work and stayed with him through the day. It returned on the drive home and lingered on weekends. He began paying closer attention to the parts of the job that felt consequential and the parts that felt procedural. The difference bothered him more than he expected.

It was around this time when regulators had started pressing banks to think seriously about environmental exposure, namely what rising seas, drought and wildfire might do to property values and loan portfolios.

With newfound purpose, Howard immersed himself in the work, earning a sustainability credential through the Global Association of Risk Professionals and helping draft frameworks for how a major financial institution might incorporate climate science into its decision-making.

For a while, it felt like a bridge between two worlds: finance and conscience. Then, gradually, the urgency dissipated throughout the industry.

“Once it got politically inconvenient,” he revealed, “it was like, okay, never mind.”

The realization landed harder than the layoff had years earlier. He had assumed that if the data were clear enough, the response would follow. Instead, the response depended on something else, something he couldn’t yet see.

That’s when he started writing.

In an effort to better understand what had actually happened in the financial crisis and the years that followed, Howard began collecting and examining public documents, regulatory filings, court decisions and budget reports so he could compare official explanations with the outcomes he had seen firsthand.

Eventually, the notes grew too extensive to keep to himself. He began sending short explanations to friends and former colleagues, mainly emails that walked through one issue at a time, linking to original sources and encouraging people to read them directly. He recorded brief videos from his desk, talking through the same material in plain language.

He started calling them “breadcrumbs,” small pieces of context meant to help people find their own way through complicated events rather than rely on pundits or headlines.

“I realized I need to stop trying to fix things from inside one company and start trying to help people understand the whole picture,” he revealed.

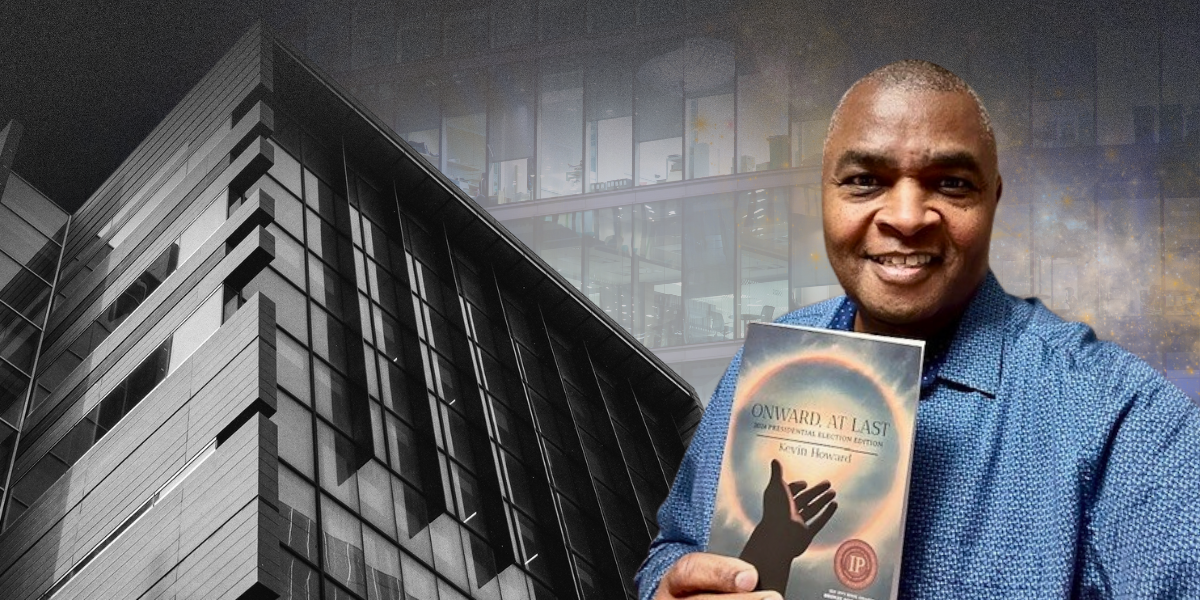

Many of those revelations made it into his book Onward at Last, a collection of essays and commentaries that blend memoir with reflections on spirituality, personal growth, economics and politics, as well as on his podcast, Breadcrumbs, where he examines and challenges the assumptions and narratives that shape modern American life.

“I don’t want people to take my word for anything,” he said. “I want them to check it themselves.”

These days, Howard runs a small climate-risk consultancy from his home in Vancouver, Washington, and much of his attention has shifted to housing, which he sees as the place where finance, climate and everyday life intersect most clearly.

His current proposal is something he calls a “price gap agreement,” a financing structure designed for people who could have afforded a home a few years ago but have been priced out by rising rates.

Under the model, investors would cover the difference between what a buyer can reasonably borrow and today’s higher sale price, taking a modest return over time instead of market-level profit. In exchange, the home would be upgraded with efficient heating or solar, reducing energy costs and emissions.

“It’s the same tools,” he said. “You just decide who they’re supposed to help.”

Howard’s story, at some level, is a familiar American arc: a professional who climbed inside an institution, prospered, watched it fracture and then stepped back to ask what the fracture revealed.

For Howard, it meant stepping away from the climb and instead putting his energy into helping other people make better sense of the system he once worked inside.

“We’re empowered to figure this out,” he said. “By starting with ourselves.”

Somewhere between the flight that landed to chaos and the morning he realized the dream felt empty, the banker who once wanted to grow businesses started trying to grow something else: a way out.